![]()

by Brian Libby

It’s easy to forget given all the upheaval that’s been going on in 2020 from pandemics to police brutality, but this year three Portland landmarks are celebrating their 20th anniversaries: the Fox Tower overlooking Pioneer Courthouse Square, the Lan Su Chinese Garden in Old Town, and the Wieden + Kennedy World Headquarters in the Pearl District.

Last fall I got a little ahead of myself and did a post about W+K’s 20th anniversary (when it was really 19 and a half), including an interview with Allied Works Architecture founder Brad Cloepfil. I’ve got an interview about the Chinese Garden with architects Nancy Merryman and Linda Barnes in the can waiting to go. But this time around, let’s talk about the Fox Tower site: both that building, completed in 2000, and the theater that stood there for 87 years prior.

The Fox Tower arrived in 2000, and yet I think of it as a 1990s building: reflective of those times and styles. It’s also a product of the 1990s economic boom. I’ve learned that any time of economic growth result in an oversized architectural presence in a city for that time period. That’s true in Portland of the early 1910s and much of the 1920s and the 1950s, for instance. The 1990s were in retrospect a kind of Pax Americana before the 21st century dramas of 9/11, Trump and the Covid-19 pandemic. There were a number of downtown buildings that arrived in this decade, but arguably the city’s most prominent 1990s building stands at the southwest corner of Pioneer Courthouse Square: the Fox Tower, a 27-story office building completed in 2000.

This is an early example of an architectural type that later became commonplace: the slender tower rising from a wider podium built to the sidewalk. The Fox Tower is also distinctive for its curving east façade, which helps minimize shadows falling over the square. Yet like a subdivision named after the landscape it replaces, the Fox Tower is named for one of the city’s most beloved old movie houses, the Fox Theatre, one of a few different names by which it was known while occupying this block from 1910 to 1997.

The Fox Theatre’s demolition left the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall as one of the sole reminders that Broadway was once lined with such theaters. While the Fox Theatre was known principally as one of the grandest Portland movie houses, it was also known (both at the beginning of the theater’s history and the end) a performance venue that hosted three of the century’s most famous names, each from a decidedly different era: Nijinsky, Monk, Cobain.

Heilig Theater postcard (Oregon Historical Society)

The two buildings standing here along Broadway over the past 110 years were the visions of two different men of the theater world a half-century apart: Calvin Heilig and Tom Moyer.

Born in Reading, Pennsylvania in 1862, Heilig ultimately came to own over 200 theaters in seven states, but the Heilig Theatre, as the Fox Theatre was originally known, was Portland’s largest upon its 1910 completion and said to be the largest west of the Mississippi with1,500 seats. Clad in brick with a Romanesque architectural style, the Heilig was designed by English-born architect E.W. Houghton, a specialist in theater designs.

The interior was appointed like an opera house, with two rear balconies as well as individual boxes along the sides of the auditorium. The most unique feature was hidden at the rear of the lower balcony: a private viewing box connected to Calvin Heilig’s adjacent upstairs apartment. That meant he could watch onstage performances from his home.

Although the Heilig Theatre principally featured traveling vaudeville theater shows and plays produced by Heilig’s stock company, in 1917 it hosted the world’s most famous ballet dancer: Vaslav Nijinsky. Over the prior decade, Ballets Russes, the company started by the legendary impresario Sergei Diaghilev, had introduced ballet to the world, with Nijinsky as star dancer

Vaslav Nijinsky (History Collection

By the time he performed in Portland in 1917, Nijinsky had spent two years under house arrest in Budapest following the outbreak of World War I, but after intervention by Diaghilev and several international leaders, the dancer was allowed to leave for New York and an American tour with Ballets Russes. Shortly after performing in Portland, however, Nijinsky’s mental condition deteriorated, and by 1919 he was committed to a mental asylum, never to perform in public again.

From the beginning, the Heilig Theatre had been equipped to show moving pictures, for a 1913 advertisement pictured in Gary Lacher and Steve Stone’s Theatres of Portland mentions “Edison’s Talking Pictures” prominently. The formal switch came in 1919, when the theater changed its name to the Hippodrome. In 1929, it was leased by the Paramount-Publix chain and changed its name again, to the Rialto. That’s when capacity for screening movies with sound was added, as well as the theater’s eye-catching marquee: a waterfall of neon lights. Beneath it was the theater’s signature island-style ticket booth, a silver-clad capsule in a Streamline Moderne style. Yet the timing couldn’t have been worse, for the Great Depression sank the new owners, who sold to the J.J. Parker chain. Now the venue was known as the Mayfair Theatre, which hosted both double-feature movies as well as stage shows.

In 1944, the Theater hosted two of the all-time greatest names in jazz: pianist Thelonious Monk and saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. At the time, Monk was a relative unknown and Hawkins was the famous bandleader, although it’s Monk that is now a Mt. Rushmore-level figure in the history of bebop jazz.

Thelonious Monk, 1947 (William Gottlieb/Wikimedia Commons)

When they arrived in town by train the group, all African-American, was refused service at the first restaurant they entered. With few Portland hotels willing to accommodate black customers, a local minister helped find local families with whom the group could stay. Ads for the Mayfair show boasted an “All Colored All Star Jazz Symphony that could play everything from Brahms to Boogie!’ On December 4, 1944, they played a matinee and evening show before moving across the river for a week-long gig at The Dude Ranch, a jazz club on Northeast Broadway in the present-day Leftbank Building.

In 1954, the Mayfair Theatre was sold and extensively renovated from a design by local firm Dougan and Heims, at which point it finally became the Fox Theatre, tied to 20th Century Fox studio. It was equipped with CinemaScope wide-screen technology, which made it the second-largest screen in the United States (trailing New York’s Roxy Theatre by two feet). For its August 12 premiere, the studio flew several of its famous actors to attend, including Van Heflin, Mamie Van Doren, Rita Moreno and Johnnie Ray. That evening the street was closed outside the theater and 2,000 spectators filled bleachers to watch the stars file in, greeted by the Rose Festival queen, to a new interior in an undersea decor theme.

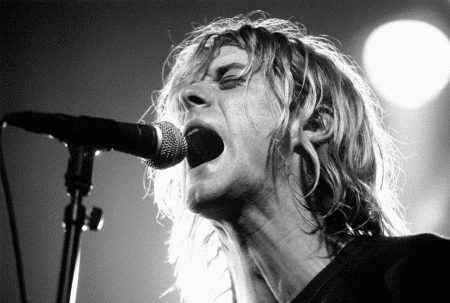

The Fox continued as a popular Portland movie house for over 35 years, with 1965’s The Sound of Music its longest-running film with a run of over two years. In 1990 the historic venue finally stopped showing movies, but as owner Tom Moyer planned and then shelved an office building on the site, the Fox Theatre continued for another seven years as a performance venue. On October 29, 1991, Nirvana and its iconic singer-songwriter Kurt Cobain played their first Portland show since the release of the band’s classic album Nevermind; it was also one month after the debut of their video for “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the song that launched Nirvana to superstardom.

Kurt Cobain (Frans Schellekens)

By that time, though, the Fox Theatre’s days were numbered because its owner had already transitioned from movies to real estate development. Born in Southeast Portland’s Sellwood neighborhood in 1919, Tom Moyer grew up working in his parents’ movie theater, where his father had gone from projectionist to proprietor. But this was also a family of boxers, and Moyer dropped out of high school to pursue a career in the ring. He ascended the ranks quickly, winning 145 of 156 amateur fights. In 1940 Moyer narrowly lost to one of the era’s greatest boxers, Sugar Ray Robinson, who today may be best remembered from the 1980 Martin Scorsese-directed classic Raging Bull. The Robinson-Moyer bout had been to decide who would represent the United States at the Olympic Games. When Robinson decided to turn pro instead, Moyer received the coveted U.S. team spot. But then the 1940 games were canceled by the outbreak of World War II. Moyer turned pro instead and won his first 22 bouts, but then quit to join the Army after America entered the war. He served in the 41st Infantry Division and was awarded a Bronze Star. During that time, Moyer also his future wife, Marylin, whom he wed in 1946.

After the war, Moyer took over the family business and built the company into a large regional chain of theaters. In 1966, he founded the Eastgate Theater on 82nd Avenue in Portland, the first multi-screen theater in the region; a year later followed the nearly identical Westgate in Beaverton (where a decade later I saw classics like Star Wars and ET: The Extra-Terrestrial for the first time). The company’s growth wasn’t without casualties, for Moyer went to court with his siblings over ownership of the business. But under his leadership, Moyer Theaters at its peak included more than 350 screens, becoming one of the nation’s largest theater chains.

In 1989, Moyer sold the company to Act III Theaters (now Regal Cinemas) for $192 million. He also retained the land underneath several of his theaters, including two prominent sites on Broadway: the Fox Theater and that of the Broadway Theater just down the street. That led to demolition of the Broadway, replaced by the 1000 Broadway office tower in 1991, then the Fox Theatre demolition in 1997 and completion of the Fox Tower in 2000.

The Fox Tower became the most prominent downtown Portland building by Thompson Vaivoda Architects, which after its founding in 1984 by Robert Thompson and Ned Vaivoda—who between them brought years of experience working for the legendary Marcel Breuer and Skidmore, Owings and Merrill—had become known for designing Nike’s pioneering corporate campus in suburban Beaverton: more than 20 different buildings housing design studios, research labs, restaurants, athletic training facilities and office space.

Bob Thompson

Robert Thompson and Ned Vaivoda today (TVA Architects, C2K Architecture)

Looking back today, TVA design principal Robert Thompson sees the similarities in his two career-making clients: Phil Knight and Tom Moyer, for whom he was working with concurrently in the late ’90s as Nike pursued a major campus expansion at the same time as the Fox Tower. “Both men were very soft-spoken gentlemen, both surprisingly quiet yet clear and decisive in articulating their goals and vision,” Thompson recalls. “When they spoke, you listened.”

Coincidentally, Nike co-founder Phil Knight would not only have been familiar with the Fox Tower’s architects, with whom he worked, but also with this particular intersection and its significance, and I’m not talking about Pioneer Courthouse Square. Across the street was the original home of the Oregon Journal newspaper, in the Jackson Tower. Knight’s father served as the Journal‘s publisher for 18 years beginning in 1953. Its offices had moved out of the Jackson Tower by the time Knight was leading the paper, but this building was its original home.

Indeed, the Fox Tower was essentially designed three different times. First was Moyer’s initial unbuilt 1991 venture, with 23 floors of offices above a three-story retail podium and four levels of underground parking. But the numbers didn’t add up for Moyer and the project went cold. The second design came in 1996 when Moyer struck a deal with the city to provide a subsidized Smart Park garage underground and then wanted TVA to add an additional six levels of above-ground parking. But city leaders convinced Moyer to cut a deal with Act III Theaters (now Regal Cinemas), the very chain to which he had sold Moyer Theaters, to add a ten-screen multiplex to the podium instead.

“That came very late in the design process but it allowed us to get rid of the above-grade parking which we were struggling with in terms of how to elegantly incorporate it into the massing and form of the tower,” Thompson says. “It was a fabulous programmatic change that lead to a complete redesign of the building at that point.”

The podium was a response to an earlier generation of downtown office buildings, all of which lacked ground-floor retail space. Office buildings of the 1960s had been set back from the sidewalk and did little to encourage active street life. The Fox Tower took advantage of its prominence to Pioneer Courthouse Square to attract large retailers with its podium’s two-story glass retail frontage. “For me the retail connection to Pioneer Square as well as how pedestrians experienced the building at the street level was critical to the success of designing a tower that activated and energized the city both in the day as well as night,” says Thompson. “When I drive up Broadway at night, I am still taken by the degree of transparency, the bright lights and the energy that radiates from the retail stores that occupy the base of the tower.”

L-R: The Fox Tower and TVA’s later Park Avenue West (Hoffman Construction)

The Fox Tower’s curving northeast façade, which makes the otherwise boxy office building distinctive, was a response to city regulations. “The city zoning code at that time did not allow any shadow from the tower to be cast directly onto Pioneer Square on April 21 at noon,” the architect recalls. “This condition quickly became a positive in the development of the tower design. The building is a simple rectangle in plan but with the introduction of the soft curve in the curtain wall, it energized the form of the building.” It also gave them leverage with their client. “Every project we designed for Tom Moyer looked to maximized the available FAR [floor-area ratio] that was allowed on the site. That was one of his most important programmatic goals,” Thompson recalls. “I loved Tom. As a developer he was very much driven the economics of the bottom line, so every square foot counted. He was quick to let you know what the loss in rent looked like over a 10 to 20-year period for every square foot of area not incorporated into the building design.”

The curve at the top of the Fox Tower is part of a broader trend I call the ’90s Curve. Every central-city building I can think of that was constructed in that decade featured some kind of curving roof or façade, although always as part of an overall rectilinear form. Other ’90s buildings like 1000 Broadway or the Hatfield U.S. Courthouse felt gimmicky, but at the Fox Tower, the curve is what brings the design alive. Perhaps that’s because it’s not just pure aesthetics like a barrel or dome-shaped roof but instead it’s a functional move.

“I would say the reason you feel positively about The Fox’s radius and curvature is because it has a purpose,” Ned Vaivoda explains. “The radius portion of the façade is a clear and direct response to mitigating shadows on Pioneer Square. When you consider the others, most are largely form-driven and lacking a fundamental purpose. While the Fox’s radius is firstly functional and intentional, there is a thoughtful and formal composition of the tower elements that unite the radius and the orthogonal. The Fox is a 26-story building adjacent to the City’s most celebrated public space. I think that purpose is legible, and that’s why you find it compelling.”